Named for the colourless nature of foods like pastas and tarts, cucina bianca is a pastoral cuisine that has fallen out of favour. However, one chef is breathing life back into it.

To make sügeli, a fresh shell-shaped pasta, chef Patrick Teisseire first takes a tiny round of dough, rolls it in flour, and with his thumb, presses it flat and slides it along a large circular wooden board. After pressing along the ridged board, a soft, contoured shell with seven fine pleats emerges. It’s a finely-honed technique that Teisseire described as the “skill of sügeli”. He repeats the process until his dough has disappeared, replaced by neat rows of pasta shells ready to be fed into a deep saucepan of boiling water.

Composed of flour, water, salt and olive oil, sügeli is one of the main dishes of cucina bianca (white cuisine), the food of the pastoral transalpine communities in the high valleys of Piedmont, Liguria and the Alpes-Maritimes in what is today south-eastern France and north-western Italy. Named for the “colourless” nature of staple ingredients, such as flour, potatoes, leeks, turnips, dairy products and legumes, it’s a cuisine that shares little resemblance to the bright reds, greens and yellows of the tomato, pepper and courgette-infused dishes of the coastal Mediterranean cuisine typically associated with the region. “An absence of colour doesn’t mean an absence of taste, however,” Teisseire was keen to emphasise as he expertly manipulated more sügeli shells from a new batch of dough in front of me.

A short time later, having swapped his small basement workspace for the dining room above it, I was ready to test his theory. Served alongside a succulent osso bucco-style veal shank and drizzled with the cooking juices of the meat, I scooped up a forkful of sügeli. Similar in size and shape to southern Italy’s orecchiette pasta, but with the texture and taste of a dumpling, the shells were the ideal shape to mop up the salty, flavoursome broth-like sauce.

Inscribed on the list of France’s patrimoine culturel immatériel (intangible cultural heritage) since 2009, sügeli is cucina bianca’s most celebrated dish. Other “more elaborate” recipes, as Teisseire described them, include green, lasagne-like strips called lausagne made from wild spinach, eggs, flour, salt and small quantities of potato and olive oil; and tantiflusa, a tart filled with potatoes, leeks and squash. Of course, cheese from local sheep figures prominently, too: alongside the hard tomme-style variety, brousse, a pungent cream cheese made from whey is a speciality of the local Brigasque breed and is often melted down into a sauce to accompany sügeli.

Sügeli is one of the main dishes of cucina bianca (Credit: Auberge Saint Martin)

I had made the 80km, or one-and-a-half-hour journey, from my home near Nice to the Auberge Saint Martin, Teisseire’s hotel and restaurant in the small mountain village of La Brigue, in the days before the property shuttered for winter last November (the new season starts in April). By the time I arrived, the early afternoon sun had already disappeared behind the towering mountains that frame the village’s riverside setting, but the warm yellows and pinks and pastel blues and greens of the Italianate trompe l’oeil facades saved the cobbled streets from feeling dark and shaded.

According to modern border lines, La Brigue is one of France’s most eastern outposts. Italy is within touching distance – less than 8km away as the crow flies. In reality, however, the concept of nationality is much more fluid for the current population of 800, some of whom were born before the village passed from Italian into French hands in a post-World War Two treaty signed in 1947. When it did, a collection of six mountain hamlet communities, including La Brigue, was cut in two administratively but not culturally.

This was evident, as tables of Algerian War (1954-62) veterans and their wives sharing the dining room with me at lunchtime proved. As they gathered to mark Armistice Day (November 11), their renditions of traditional Piedmontese songs were a rousing soundtrack to my meal. “This is still an important local custom because, until 1947, the village was part of Piedmont,” Teisseire told me.

Teisseire, who was born and raised in La Brigue, ran the local pizzeria until the opportunity came to take over the inn on the main square eight years ago. This new start gave him pause to reflect. “I asked myself, what exactly is our local cuisine?” he explained.

Patrick Teisseire serves sügeli with an osso bucco-style veal shank (Credit: Rémy Cortin)

The answer was just outside his door, in the high pre-alpine pastures where the Brigasque still graze during the warmer months. “I realised that absolutely all the cuisine that is practised here has a link with milk, sheep, shepherds and transhumance,” he said. “So, I decided to bring that back to the kitchen and showcase it.”

At the heart of cucina bianca is the practice of transhumance, or moving herds from the mountains to the coast. In autumn, after a summer spent grazing on grassy mountain slopes, shepherds and their families would traditionally guide their flocks towards the warmer coastal pastures for winter. By spring, they would be ready to return back inland.

I realised that absolutely all the cuisine that is practised here has a link with milk, sheep, shepherds and transhumance.

To feed their families along the way, shepherds’ wives cooked over a chimney fire in rustic shelters called malghe dotted along the route. With 1kg of flour alone, these resourceful women could make enough food to feed 10 people. “Meals usually involved just one dish that wasn’t complicated or time-consuming to prepare, but still required a certain savoir-faire,” Teisseire said.

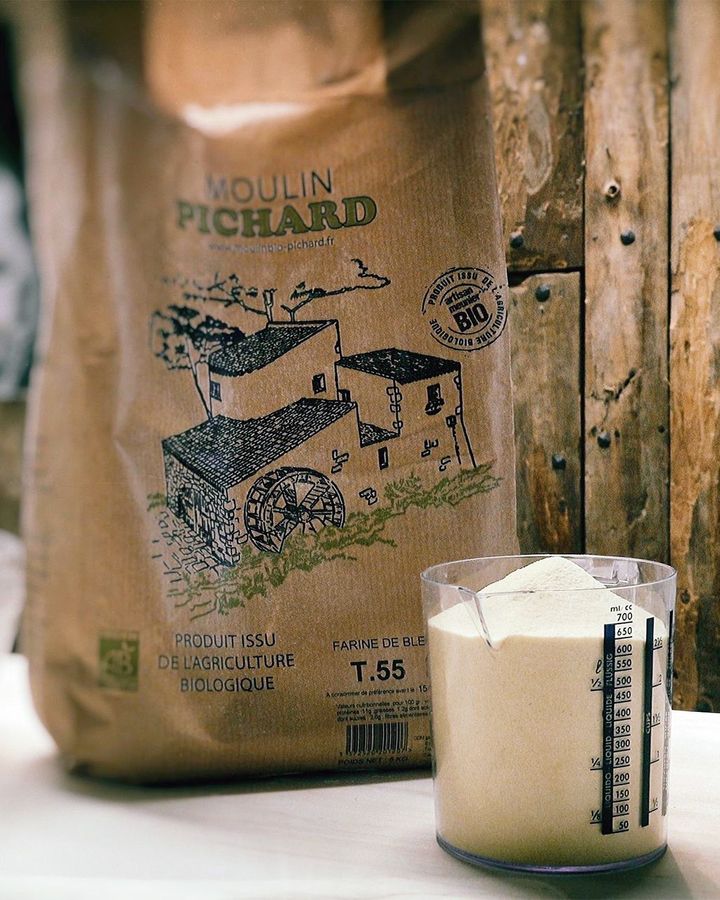

Cucina bianca is characterised by ingredients like flour, potatoes, leeks and dairy (Credit: Auberge Saint Martin)

Wild herbs collected along their path, such as nettles and borage, seasoned the dishes. By nature, it was a diet almost totally free of meat, save for the occasional rabbit or game, the latter when it was hunting season. Olive oil was another precious commodity to be used sparingly, replaced by butter or, more commonly, milk.

Transhumance was at its height in the Roya valley during the 19th and early-20th Centuries, but the practice started to die out with the post-World War One rural exodus (at its most populated in 1848, La Brigue had 4,047 residents). With her husband, Francis, Martine Lanteri is one of the few remaining Brigasque sheep breeders. “We’ve been the only ones to continue with transhumance for about 25 years now. The only other local family stopped in the 1990s,” said Lanteri.

Although four-wheeled trucks have long replaced two feet to cover the distance, the couple continued to move their herd to the Côte d’Azur towards Cannes for winter until health reasons stopped them two years ago. But today, Teisseire keeps them busy. “Every week, he’s coming back for more brousse,” she laughed.

Auberge Saint Martin is located in the small mountain village of La Brigue (Credit: Pango Visual)

For Teisseire, amid the current economic challenges and the climate crisis, this simple cuisine made from locally grown ingredients is more relevant than ever. “Cucina bianca is built around using only what is necessary and wasting nothing,” he said. “It proves that people, at the time, were much more adapted to the land and what they had to cook.”

And, as he breathes life back into a forgotten cuisine, he is also helping to revive a region that was cut off from the rest of France by devastating flash floods in 2020. The recovery from Storm Alex – which wiped out homes and infrastructure in the Roya valley and its neighbouring Vésubie valley and claimed 10 lives in the Alpes Maritimes – has been slow. But the promise of cucina bianca is drawing visitors back into the furthest corners of the valley. This summer, in partnership with a local tour operator, Teisseire is launching a week-long slow tourism itinerary along La Route de Cucina Bianca, an alpine route that links traditional transhumance communities on both sides of the French and Italian border.

“He’s created a lot of work for himself,” Lanteri said affectionately of her friend Teisseire. But driven by a passion for keeping his community and its traditions alive, he wouldn’t change anything. “For me, cucina bianca is about reconnecting with nature,” Teisseire said. “That’s what I love about it.”

Patrick Teisseire forms sügeli into gnocchi-like cubes (Credit: Auberge Saint Martin)

Sügeli recipe

By Patrick Teisseire

(serves 10)

INGREDIENTS

1kg white flour

1 tsp salt

2 tbsp olive oil

600g water

Method

Step 1

Put the flour on the work surface and make a well in the middle. Add 1 tsp of salt, olive oil and water. Using your hands, mix the ingredients together until a ball of dough forms. Form the dough into a sausage shape, about 1cm thick. Using a knife, cut into gnocchi-like cubes, about 1½cm long.

Step 2

Working on a floured wooden work surface, take a cube of the dough and turn it cut side up. Press it down with your thumb, then gently pull along the ridges (if there are any) of the wood surface with your thumb until you get a sügeli with seven pleats (or until the dough takes on the shape of a shell; making classic sügeli with its pleats takes practice to perfect and requires a ridged wooden work board). Repeat to form the remaining sügeli.

Step 3

Bring a pot of salted water to a boil and cook the shells for approximately 10 minutes, but taste to check for doness as they are cooking. The shells are ready when they are floating and are just a little hard to the bite (al dente).

Step 4

Drain, reserving ⅓ cup of the cooking water. Transfer the sügeli to a saucepan set over medium heat and add the reserved cooking water. Simmer for 5 minutes, or until the sügeli absorb the water. Season to taste and drizzle with extra virgin olive oil. Serve as an accompaniment to osso bucco or a hearty winter stew (drizzle with the cooking juices for extra flavour).

Source : BBC